Startup Tips from Clever's CEO

Tags: startups, ed-tech, economics/business

One month ago1, I attended a speaker event at UC Berkeley about ed-tech startups. The speaker, founder and former CEO of Clever Tyler Bosmeny, gave a lot of good advice about running companies. Since I’m currently looking for cool, technology-related topics to write about, I’ve decided to compile my notes on this subject and publish it as a blog post (or, in my personal lingo, a “VJPost”).

Here’s what I learned from the talk:

Background info: What is Clever?

Tyler started off the speaker event by explaining that Clever is an educational technology company that provides single sign-on, software setup help, and many other technology integrations for schools.

With a team size of 210 people, Clever is used by over half of K-12 schools in the US. Even more surprising is that of the 100 largest school districts in America, 97 use Clever.

It was funded by Y Combinator in 2012, and in 2021 it was acquired by Kahoot.

Their most well-known product is the single sign-on platform, which I remember using a lot in high school.

1. An interesting monetization model

American and Canadian schools aren’t charged anything for using Clever’s platform unless they specifically opt-in for some extra add-on features. The company instead generates revenue by asking other ed-tech tools, e.g. Google Classroom or Aeries (a tool used to track student grades and attendance) to pay to be integrated into Clever. It’s a win-win for all parties involved since schools pay nothing, Clever makes money, and the apps integrated into Clever get more users.

2. The team had domain expertise

One of the co-founders of Clever, Dan Carroll, worked as a teacher and later as an IT Director at a school in Denver, Colorado. As a result, the team had a clear sense of what kind of product teachers would actually use. This also prevented the founders from creating a product that sounds good on paper but wouldn’t actually work. In other words, “specific knowledge” played a crucial role in the development of Clever’s product. Coined by entrepreneur and angel investor Naval Ravikant, specific knowledge is a type of intuition that is gained through real-world employment or apprenticeships and is crucial to launching startups in domain-specific areas like ed-tech.

One other thing: a common mistake Tyler warned about is assuming that because most of us have gone through school as students, we don’t need any additional experience to differentiate between good and bad ed-tech ideas.

3. International acquisitions = lots of bureaucracy

During the pandemic, Kahoot offered to acquire Clever for $500 million. There was just one issue: bureaucracy. Since Kahoot is a Norweigan company, the US government was not happy that students’ (potentially sensitive) educational data was being handed over to other countries. For a while, the founders were concerned the deal wasn’t going to happen. But then one day, the team randomly got a call from the company lawyer, saying that the acquisition had been OKed.

The bureaucracy surrounding international acquisitions is very complex, and the history behind all of this is pretty interesting. It started in 1980s when there was widespread fear that American industries would get acquired by companies in other countries, especially Japan. For example, Fujitsu offered to acquire Fairchild Semiconductors, a pretty notable company at the time. This caused a little bit of panic in the United States, and in response, the Exxon-Florio amendment was passed. The law allowed the U.S. President to block any “foreign investment” deemed a threat to national security. It also expanded the power of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or CFIUS, the same organization that later oversaw the Kahoot acquisition.2

Another thing I’m curious about is, what kind of regulations exist for ed-tech companies in America, and how do they affect the kinds of ideas that founders are willing to take a risk on?

4. High valuation isn’t always a good thing

Clever’s initial fundraising rounds were very successful.

Their Series A, for example, raised over $10 million USD through Sequoia capital.

Investors were impressed and the team was enthusiastic.

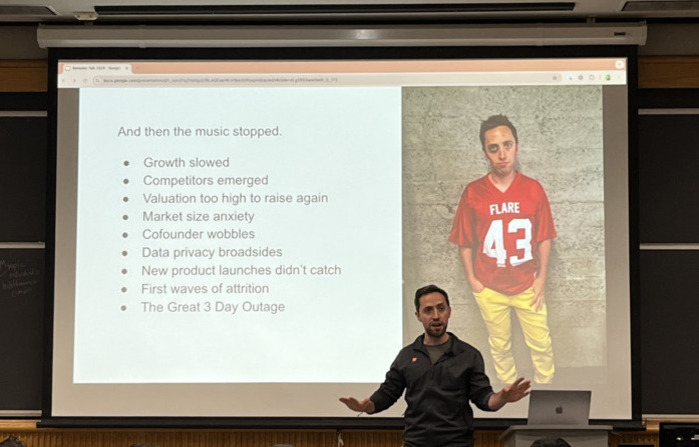

A few years after launching, though, the company ran into a problem:

because they’d already raised so much money, their valuation was “too high to raise again”.

(If anyone can find a news article or website which more thoroughly explains how Clever’s valuation was too high to raise again, how they dealt with this issue, and the long-term implications for the company, please reach out!)

A few years after launching, though, the company ran into a problem:

because they’d already raised so much money, their valuation was “too high to raise again”.

(If anyone can find a news article or website which more thoroughly explains how Clever’s valuation was too high to raise again, how they dealt with this issue, and the long-term implications for the company, please reach out!)

Related: some platforms avoid seed funding altogether but end up successful anyway. For example, Dingboard was successfully bootstrapped even though the product is a compute-intensive, (presumably very expensive) AI-powered image editing tool.

5. Downtime bad

In The Social Network, there’s a scene where Mark Zuckerberg panicks over Facebook’s servers going down. He yells at his cofounder for causing the site to go down, complaining that even a short window of downtime would irreparably destroy The Facebook’s reputation and make it look “uncool.”

The Social Network is a dramatized movie, but I don’t think fictional-Zuckerberg was far off when he warned about the dangers of downtime. In the case of Clever, going down for just three days was enough to cause a mini-disaster for the company, complete with phone calls from upset school principals and long hours spent debugging technical issues. To make matters worse, the downtime happened during standardized testing season.

Luckily, the incident was resolved and from then on, it was referred to as “The Great Three-Day Outage”. (You can actually see this phrase at the bottom of the image from about how high valuation can hurt startups.)

6. A startup can be a “better mousetrap”

Clever’s signature product, the single sign-on platform, didn’t require a scientific breakthrough to implement - instead, the founders connected together existing technologies with a straightforward, easy-to-use interface.

There are many other examples of successful platforms which boil down to connecting other technologies together in a seamless, well-integrated way. Some examples of this include ChatGPT plugins, GPT wrappers (which, despite much negative press, can be profitable) and low-code platforms for computer vision (e.g. Datature). Here’s another cool example: one of my classmates at Berkeley is working on a startup, ezML, to make it fast and cheap to deploy computer vision apps.

Conclusion

The talk lasted less than two hours, but I felt like a got a lot of out of it. Moving forward, I’d like to better understand what makes technology businesses succeed and fail. Besides the actual product a company produces, what else determines its success or failure?

Thanks for reading my second blog post! If you loved (or hated) reading it, please reach out over email or leave a comment below.

-

As for why I’m posting this one month late: When I got home that night from the speaker event I made a solid two pages of notes about all the interesting things he said. I posted about it on Airchat and made a mental note to write a blog post about it later. But then, final exams rolled around and I forgot about the post. Fortunately, a few weeks later stumbled upon my notes about Clever while flipping through my notebook. ↩

-

Source 1 (info about CFIUS), Source 2 (Fairchild semiconductors acquisition), Source 3 (Exxon-Florio amendment) ↩